Introducing the baren, and its construction

(entry by Bill Paden)

Editor's note: Mr. Paden gave permission to use this material, provided that the following 'conditions' were met:

- "... present it in its ENTIRETY IN ONE PIECE ..."

- "... Hidehiko Goto to be mentioned up front as 'a generous source and respected baren maker'..."

- "... was originally published by McClain's Printmaking Supplies, Portland, Oregon, 1992 ..."

There is no such thing as THE baren. Rather, there are many different kinds of barens, each made for a special purpose. Which baren(s) you need depends upon several related factors: the kind of washi being used; the technique employed; the kind of cutting done on the block; the size of the color area to be barened; and finally, the depth of your pocketbook. Although the latter is not really a need, it's certainly a factor to consider.

There is a plethora of barens on the market to choose from; small kiddie barens and cheap imitations, carried by many art stores that cost a few dollars. These, however, are of no use, a total waste! There are also substitute barens made of ball bearings, plastic, synthetic string, etc. These are of great interest, but ...

Our focus is upon the professional hon baren which is made up of 3 parts; the barengawa wrapping, the ategawa backing disk, and the shin core, listed in reverse order of importance and cost.

- TAKENOKAWA (bamboo sheath). Not all takenokawa are good for wrapping. Some are too thin, too narrow or too stiff. One common bamboo species of the several hundred that exist - madake - provides a kawa that is well suited for wrapping. As an aside, it is best to keep the takenokawa in a damp place to prevent it from drying out and cracking. If the kawa does develop minor cracks, it can still be used. Simply repair it with Scotch tape on the inner side right before it becomes the barengawa.

- ATEGAWA (backing disc with a slight rim). The ategawa, simple in material and design (paper mache), is truly a work of art. Several of its unique features are not apparent to most eyes. First, it is not a flat disk, but is made slightly convex to produce more concentrated barening pressure. Second, prior to lamination the washi (Japanese paper) is treated with kakishibu, tannin juice from a half-ripe, non-edible persimmon, to assure it is waterproof. Third, laminating the 39 to 49 layers of washi over the course of 9 months to a year (waiting time - 2 to 7 days - between each pasting takes time) is NOT done with rice nori. Rather, the key to success of the ategawa's construction - very light, long lasting, flexible to a degree but non-warping - is warabi nori, a paste made from the flour of the fiddlehead fern. This warabi nori is extremely strong, and above all, it has no body; thus the thinness of the ategawa. Those made with any other nori are thick, heavy and clumsy - all things you don't want in a baren. Since the ategawa is difficult to make properly, consumes an inordinate amount of time and hardly pays a living wage, the search is on for a substitute. One respected baren maker has come up with a solution called the Ki-urushi baren. The ategawa is milled out of 5-ply shina plywood, beautifully lacquered black and presented in a handsome wooden (kiri) box. Also, reducing the size of the hon baren from its standard 5 1/4" to 5 1/2" size to 4 15/16" (or even smaller, 4 5/8") helps reduce the cost. Whether it will have a longer life than the traditional washi ategawa, as claimed, is open to question. Check back in 25 years!!

- SHIN, pronounced shen, (core). The cord that is coiled in a flat spiral is the guts of the baren. Set in the ategawa and held together with the barengawa, it provides many nodes or contact points for printing. It is these multiple points of contact that drive the color on the block up into the fibers of the washi, in effect dying it. There are 3 general types of hon baren, each determined by the number of strands twisted together to form the shin. There are several different sizes of each strand, which are determined by the width of the strips used to make them. The variation in sharpness of the nodes and in the resulting coiled density of the shin differentiates one baren from another.

Types of the hon baren

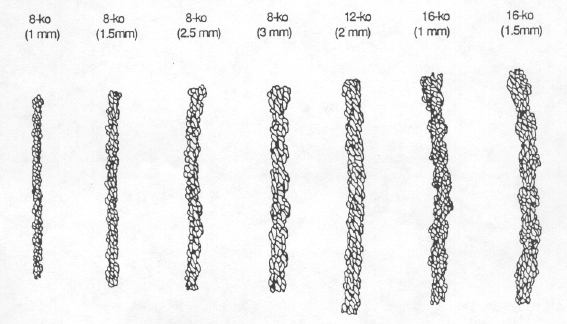

The 3 types of shin/baren are: 8 strand, 8-ko (Yakko); 12 strand, 12-ko (Juniko); and 16 strand, 16-ko (Jurokko). In addition, most baren makers produce four to six sizes of 8-ko, one or two sizes of 12-ko and one or two sizes of 16-ko. A 4 strand, 4-ko (Yonko) can, of course, be made, but is almost never used. It is just not as good as the 8-ko.

Making of the shin begins with two small, strong and even sections of the kawa of the shiratake (white bamboo), about 1 1/2" by 8". They are cut out and reserved. The rest is discarded.

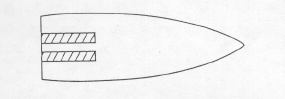

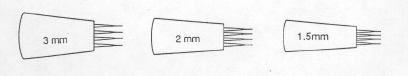

After further preparation, the two sections are cut into thin strips. Each baren maker fashions his own cutting tools out of sharp needles (or something of the sort) set in a wooden handle.

There is a tool for cutting strips of each of the different sizes: 3mm, 2.1mm, 2mm, 1.5mm and 1mm. There is even an incredibly fine 0.6mm tool. The strips are tied together and twisted, twisted and tied until a long thin cord is formed. After more twisting and tying, the finished cord is coiled and tacked together with thread to form the shin, which is then put into the ategawa.

8-ko BARENS (Yakko)

The cord has prominent nodes that permit strong baren pressure.

|

|

|

| |

|

1 |

3 mm |

extra thick |

For thick washi like torinoko; very strong pressure on wide color areas |

|

2 |

2.5 mm |

thick |

Normal to thick washi; strong pressure. |

|

3 |

2 mm |

medium |

Most useful, standard baren; good for many techniques and for thin to medium washi. Not for thick washi. |

|

4 |

1.5 mm |

fine |

Thin washi; detailed blocks. |

|

5 |

1 mm |

extra fine |

Thin washi; very fine detail like an ukiyo-e key block. |

|

6 |

0.6 mm |

super fine |

Suited for the most delicate lines and areas. |

12-ko BARENS (Juniko)

Relatively smooth nodes prevent baren-suji.

|

|

|

| |

|

1 |

2 mm |

medium |

Won't cause baren-suji; depending upon the pressure, can be used for various kinds of printing, even delicate work. Not good for large area tsubushi. |

|

2 |

1.5 mm |

fine |

Not the same as 8-ko (1 mm), but still good for delicate work. |

16-ko BARENS (Jurokko)

More prominent nodes than the 8-ko barens. Best suited for very strong pressure.

|

|

|

| |

|

1 |

1.5 mm |

medium |

For very thick washi and large color area tsubushi and urazuri; the baren most suited for strong pressures. |

|

2 |

1 mm |

fine |

Similar to above, but less chance of getting baren-suji. |